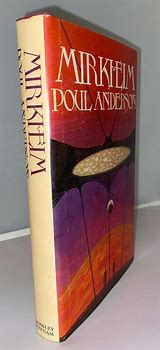

Mirkheim, IX.

We have discussed the Council of Hiawatha. The Solar Commonwealth legislation to which this Council of the Polesotechnic League acquiesced had the following effects, among others:

"Regulatory commissions soon turned into creatures of the industries they regulated - and discouraged (at first) or stifled (later) all new competition. This was much aided by a tax structure heavily weighted against the middle class. After a while, the great bankers were not just handling money, they were creating it with a vested interest in inflation." (pp. 141-142)

The three quoted sentences are part of a condensed five-page summary and need some unpacking. Does that tax structure aid that stifling of competition by discouraging new investment? Do bankers not always create money by lending money that is not theirs, by lending more than is in their possession and by charging interest on it? They were not merely "handling" other people's money before the days of the Solar Commonwealth. Why should they have a vested interest in inflation if they can make profits without it?

The omniscient narrator sees the main problem as:

"...that large percentage of mankind that had never really wanted to be free." (p. 140)

What is this statistic based on? Not everyone either can or wants to be free like van Rijn. But a greater degree of individual and collective self-determination is a realistic and maybe increasingly necessary goal.

13 comments:

Even with a faster-than-light propulsion technology, one wonders how a banking system that depended on - essentially - the mail to be delivered from one inhabited world to another would function as much of anything beyond the world it called home and - perhaps - the rest of a given solar (lower case 's') system.

Oh, the banking's not a problem. The Bank of England, for example, operated all over the world when it took months to get from A to B, and a sailing ship was the fastest way to deliver a letter.

For that matter, Roman bankers in the 2nd century (I've been researching that for a book) did transfers of money and credit by letter over thousands of miles.

Eg., you could deposit money in a bank in Carnuntum, and then draw on it from a bank in Sirmium, which was about a week's travel away, with a sealed authorization from the original bank.

My impression is that some sorts of fraud involving cheque kiting became harder to do as communications became faster, or it became less necessary for the banks to have explicit ways to combat those forms of fraud.

Jim: yes, but preprinted checks in our sense only became common in the 20th century.

(Percusors had existed for a long time and -- very gradually -- became more common over time. Originally, checks only circulated locally to people who could 'check' the signatures from previous documents.)

Note: regulatory capture is a genuine phenomenon, albeit not a universal one. Between the 1930's and the 1950's, it happend on a fairly substantial scale in the US, and the companies concerned did use it to quash the competition.

Eg., take the relationship between Ma Bell and the FCC in that period.

Not certain the BofE was doing much commercial banking - as opposed to central bank type functions - outside of the UK and - at most - the North Atlantic littoral during the Age of Sail; the Rothschild and Baring interests were the first really international merchant banks, and even most of their efforts in the 18th and early 19th centuries were based on business in the UK and western Europe. Same for Hope & Co., in Amsterdam.

True global banks came into being during the late 19th Century, largely because of steam and transoceanic cable networks - and even then, they routinely went under (or came close) because of various bubbles due to distance and fraud.

The global trading companies - the British and Dutch east indies companies, for example - conducted business at global distances during the Age of Sail, but that was not banking; to a large degree, it was legalized piracy turned resource extraction and trade of said resources, and given the technical superiority of the Europeans, it did not take much in the way of business management skill to turn a profit - although bubbles and failures were legion from the South Seas to Darien and back again.

I lean more to Stirling's views here. Given the examples of Roman banking and the Bank of England, financial transactions carried out over interstellar distances should be possible in the Technic series.

Ad astra! Sean

Given Technic levels of tech (8-)) I would expect automated "message shuttles) between important solar systems -- they pop out of hyperspace, blip out streams of condensed data, get beamed and record the analogues locally, then blip back to the source. Or do routes. The equivalent of the Pony Express.

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

I think we should assume that to be the case. See as well Roan Tom's hypothetical comments on how the disintegration of information collating services worsened the chaos after the Empire fell in "A Tragedy of Errors."

Ad astra! Sean

automated "message shuttles"

L.M. Bujold included that in her "wormhole nexus" where the amount of message traffic justified it. An automated shuttle would hop through the wormhole, beam messages to any worlds or habitats, and receivers at other wormholes in the system, receive messages and carry them back through the wormhole.

I don't recall that existing anywhere in Pournelle's Codominium/Empire of Man series or a justification for why that wouldn't work with the Alderson drive.

Similarly in the "Antares Dawn" series Michael McCollum, although people sometimes put 'space forts' at 'fold point' exits, something that would make sense in at many places with Pournelle's Alderson drive, he didn't include such message shuttles

Kaor, Jim!

Good point, what you said about Pournelle's Co-Dominium timeline stories. And I otherwise consider the Co-Do stories to be one of the better future histories.

Ad astra! Sean

S.M. - Looking for historical analogues when it comes to fictional technology is always questionable, but even the subsidized "mail" maritime services (Royal Mail contracts for Cunard, the Pacific Mail in the US, etc.) began in the 1840s, in the steam era.

Global banking was not really practical until steamships and telegraphy using oceanic cables - which wasn't really a thing until the mid-19th Century, either.

Absent a technology beyond shipping, even FTL shipping, banking presumably would be limited because of the physical limitations of RF technologies.

Post a Comment