I strive to appreciate the physical settings of the fictional events in Poul Anderson's works, e.g.:

the city of Archopolis in Dominic Flandry's period;

the environments of planets like Diomedes, Avalon, Aeneas, Imhotep and Daedalus;

the city of Inga on the planet Asborg in For Love And Glory.

By taking notes on what we are told, I usually find that the characters move through a fully realized and consistent environment. In fact, the author has usually imagined more than we are shown in the action of a single novel. In prose fiction, the author must do all of this creative work himself, although he might acknowledge advisers.

Visual media are more collaborative. In a film adaptation, how many people would design the costumes worn in Archopolis? Dave Gibbons, who drew Alan Moore's Watchmen, writes:

"Whilst Alan was coming up with new character names and backgrounds, I thought about the ways Watchmen's alternate world differs from ours and presented him with notes about fashions, social and scientific changes, and so on. I mentioned the idea of pirate comics, reasoning that a world with real super heroes would have no need of them in comics."

-Dave Gibbons, Watching The Watchmen (London, 2008), unnumbered page.

This comparison of Anderson's prose novels with Moore's and Gibbons' graphic novel is not as fanciful as it may appear because Gibbons had written a few pages previously:

"I had an epiphany one day when I realized that Watchmen was not a super-hero book as such, but rather a work of science fiction, an alternate history."

Watchmen shows its readers an alternative New York just as an AI "emulation" in Anderson's Genesis immerses two of the characters in an alternative York.

Showing posts with label Watchmen. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Watchmen. Show all posts

Tuesday, 23 February 2016

Wednesday, 25 November 2015

Poul Anderson And Alan Moore

I am reading a biography of Alan Moore with an Introduction by Michael Moorcock: from the sublime to the sublimer. What do Poul Anderson and Alan Moore have in common?

(i) Although primarily a graphic novelist and comic strip script writer, Alan has also written prose fiction: some short stories, a novel, Voice Of The Fire, and a second novel, Jerusalem, to be published in Spring 2016.

(ii) Alan has written historical fiction (Voice Of The Fire) fantasy (Promethea) and sf (Halo Jones; Skizz). Voice Of The Fire features Romans ("Men of Roma") in Britain.

(iii) He received a Hugo award for Watchmen.

Differences

(i) PA and AM are at opposite ends of the political spectrum.

(ii) Whereas Anderson seemed sympathetic to the monotheist faiths, Alan practices magical rituals and worships the Roman snake god, Glycon. (He doesn't want his fans to copy his religion and I don't!)

(iii) Whereas I saw Anderson at a couple of sf cons, I have met Alan briefly a few times. (In fact, following clues in his published works, I found my way to his front door.)

(iv) Alan taught comic script writing to Neil Gaiman and I have found several parallels between Anderson and Gaiman, less between Anderson and Alan. Nevertheless, these three men are major modern imaginative writers.

(i) Although primarily a graphic novelist and comic strip script writer, Alan has also written prose fiction: some short stories, a novel, Voice Of The Fire, and a second novel, Jerusalem, to be published in Spring 2016.

(ii) Alan has written historical fiction (Voice Of The Fire) fantasy (Promethea) and sf (Halo Jones; Skizz). Voice Of The Fire features Romans ("Men of Roma") in Britain.

(iii) He received a Hugo award for Watchmen.

Differences

(i) PA and AM are at opposite ends of the political spectrum.

(ii) Whereas Anderson seemed sympathetic to the monotheist faiths, Alan practices magical rituals and worships the Roman snake god, Glycon. (He doesn't want his fans to copy his religion and I don't!)

(iii) Whereas I saw Anderson at a couple of sf cons, I have met Alan briefly a few times. (In fact, following clues in his published works, I found my way to his front door.)

(iv) Alan taught comic script writing to Neil Gaiman and I have found several parallels between Anderson and Gaiman, less between Anderson and Alan. Nevertheless, these three men are major modern imaginative writers.

Tuesday, 21 July 2015

Oblique Commentaries

Works of fiction set in alternative histories obliquely comment on what we regard as real history.

(i) In a British TV play with the premise that the Germans won World War II, a man making a TV drama about the War said, "I can't rewrite history..."

(ii) In Poul Anderson's Operation Luna, cooperation between Einstein and Planck released forces previously regarded as magical. What would have happened if they had continued to work separately?

(iii) In Alan Moore's Watchmen:

when a superhero has won the Vietnam War for the US, someone remarks that, if we had lost this war, we would have gone mad as a nation;

two journalists called Bernstein and Woodward are found dead;

the headline "RR to run for President?" is greeted with the question, "Who wants a cowboy actor in the White House?" Of course the headline refers to Robert Redford.

(iv) In SM Stirling's The Peshawar Lancers (New York, 2003), Warburton remarks that, if the Fall had not thrown back progress, then by 2025 the world would be beyond the possibility of a World War and might even have been united by the British Empire. Yasmini, a clairvoyant who sees alternative realities, stirs, then subsides... "Ask later, [King] thought." (p. 315)

(i) In a British TV play with the premise that the Germans won World War II, a man making a TV drama about the War said, "I can't rewrite history..."

(ii) In Poul Anderson's Operation Luna, cooperation between Einstein and Planck released forces previously regarded as magical. What would have happened if they had continued to work separately?

(iii) In Alan Moore's Watchmen:

when a superhero has won the Vietnam War for the US, someone remarks that, if we had lost this war, we would have gone mad as a nation;

two journalists called Bernstein and Woodward are found dead;

the headline "RR to run for President?" is greeted with the question, "Who wants a cowboy actor in the White House?" Of course the headline refers to Robert Redford.

(iv) In SM Stirling's The Peshawar Lancers (New York, 2003), Warburton remarks that, if the Fall had not thrown back progress, then by 2025 the world would be beyond the possibility of a World War and might even have been united by the British Empire. Yasmini, a clairvoyant who sees alternative realities, stirs, then subsides... "Ask later, [King] thought." (p. 315)

Thursday, 11 June 2015

Fictions Within Fictions

Adventure fiction sometimes refers to adventure fiction. There are two ways to do this:

(i) one fictional character referring to another, e.g., James Bond saying that he likes Nero Wolfe (Bond does say this);

(ii) fictions within the fiction.

(i) Usually, when a fictional character refers to, e.g., Sherlock Holmes, we understand that Holmes is as fictional to the character referring to him as he is to us. There are exceptions. For example, Holmes is real in Poul Anderson's Time Patrol series and in CS Lewis' Narnia Chronicles.

In SM Stirling's In The Courts Of The Crimson King, an archaeologist is unhappy when his exploits on Mars begin to resemble those of a certain whip-wielding cinematic archaeologist and, when held captive, he reflects that adventure fiction heroes locked in dungeons always escaped instead of having to be rescued...

(ii) Fictional characters can also refer to fictions that exist in their world but not in ours. Flandry says:

"'...an undertaking such as [Magnusson's] would be the most audacious ever chronicled outside of cloak-and-blaster fiction.'" -Poul Anderson, Flandry's Legacy (New York, 2012), pp. 450-451.

In a completer History of Technic Civilization, we would like to read:

one of their cloak-and-blaster novels;

media coverage of the Mirkheim crisis;

one of Andrei Simich's poems about a hero of Dennitza;

and a lot more.

Shakespeare presents more than one "play within the play." In Alan Moore's Watchmen, a comic about superheroes, a boy reads a pirate comic and we read it over his shoulder, becoming as involved with the fiction within the fiction as we are with the fiction. In our world, i.e., on Earth Real, Watchmen was dramatized as a feature film and the comic within the comic was dramatized as a short animated film. Following these Shakespearean and Moorean precedents, Anderson might have presented a cloak-and-blaster novel to be derided by Flandry for its inaccuracies and implausibilities.

Busy long weekend starting tomorrow so maybe less posts.

(i) one fictional character referring to another, e.g., James Bond saying that he likes Nero Wolfe (Bond does say this);

(ii) fictions within the fiction.

(i) Usually, when a fictional character refers to, e.g., Sherlock Holmes, we understand that Holmes is as fictional to the character referring to him as he is to us. There are exceptions. For example, Holmes is real in Poul Anderson's Time Patrol series and in CS Lewis' Narnia Chronicles.

In SM Stirling's In The Courts Of The Crimson King, an archaeologist is unhappy when his exploits on Mars begin to resemble those of a certain whip-wielding cinematic archaeologist and, when held captive, he reflects that adventure fiction heroes locked in dungeons always escaped instead of having to be rescued...

(ii) Fictional characters can also refer to fictions that exist in their world but not in ours. Flandry says:

"'...an undertaking such as [Magnusson's] would be the most audacious ever chronicled outside of cloak-and-blaster fiction.'" -Poul Anderson, Flandry's Legacy (New York, 2012), pp. 450-451.

In a completer History of Technic Civilization, we would like to read:

one of their cloak-and-blaster novels;

media coverage of the Mirkheim crisis;

one of Andrei Simich's poems about a hero of Dennitza;

and a lot more.

Shakespeare presents more than one "play within the play." In Alan Moore's Watchmen, a comic about superheroes, a boy reads a pirate comic and we read it over his shoulder, becoming as involved with the fiction within the fiction as we are with the fiction. In our world, i.e., on Earth Real, Watchmen was dramatized as a feature film and the comic within the comic was dramatized as a short animated film. Following these Shakespearean and Moorean precedents, Anderson might have presented a cloak-and-blaster novel to be derided by Flandry for its inaccuracies and implausibilities.

Busy long weekend starting tomorrow so maybe less posts.

Saturday, 6 June 2015

Chaotic Terrain

Brian Aldiss wrote somewhere that human beings have successively populated first the Terrestrial environment, then the the Solar System, then other planetary systems, with nonhuman intelligences. He thought that, in all three cases, human qualities were being projected onto the external universe: anthropomorphism.

Poul Anderson would have welcomed human-alien contact but, with systematic thoroughness, wrote fictional accounts of interstellar exploration both with and without such contact. SM Stirling's "Lords of Creation" series, with its populated Venus and Mars, is wish fulfillment fiction. Alan Moore's post-organic, post-mortal character, Doctor Manhattan (see image), teleports to Mars where, when asked about the significance of life, says that he prefers:

chaotic terrain;

Mons Olympus;

the four miles deep, three thousand miles long, Valles Marineris, with day at one end and night at the other, where temperature differences cause shrieking winds to herd oceans of fog.

But then he is persuaded to value the thermodynamic miracle of each individual human birth.

Poul Anderson would have welcomed human-alien contact but, with systematic thoroughness, wrote fictional accounts of interstellar exploration both with and without such contact. SM Stirling's "Lords of Creation" series, with its populated Venus and Mars, is wish fulfillment fiction. Alan Moore's post-organic, post-mortal character, Doctor Manhattan (see image), teleports to Mars where, when asked about the significance of life, says that he prefers:

chaotic terrain;

Mons Olympus;

the four miles deep, three thousand miles long, Valles Marineris, with day at one end and night at the other, where temperature differences cause shrieking winds to herd oceans of fog.

But then he is persuaded to value the thermodynamic miracle of each individual human birth.

Sunday, 24 May 2015

Today

OK. I have been laid up all day with yet another cold. Lying in bed, I have reread some more of Poul Anderson's Starfarers but not yet been motivated or inspired to post. Of the human explorers:

Kilbirnie is killed when she pilots a boat too close to the accretion disk of the black hole;

Brent mutinies and thus does what I would have thought was impossible, reintroduces armed conflict between a handful of characters in an STL spaceship exploring a black hole thousands of light years away from Earth.

I have already posted about the quantum intelligences composed of virtual particles in the gravitationally distorted space near the black hole and also about social conditions back on Earth when the Envoy returns millennia later but will continue to reread the novel, expecting to notice some new details in the remaining 100+ pages.

I have also reread much of Alan Moore's Watchmen. Both of these very dissimilar authors are masters of several genres, albeit mainly in different media. I have listed Anderson's genres more than once before. It may be of interest to compare Moore's slightly different list:

Anderson

science fiction

fantasy

historical fiction

detective fiction

historical fantasy

heroic fantasy

historical sf

humorous sf

maybe two ghost stories?

Moore

science fiction

fantasy

horror

superheroes

fictional ads and political propaganda

a historical novel

a ghost story

pornography

contemporary fiction

a screen treatment

Someone will now tell me what I have missed from either list.

Kilbirnie is killed when she pilots a boat too close to the accretion disk of the black hole;

Brent mutinies and thus does what I would have thought was impossible, reintroduces armed conflict between a handful of characters in an STL spaceship exploring a black hole thousands of light years away from Earth.

I have already posted about the quantum intelligences composed of virtual particles in the gravitationally distorted space near the black hole and also about social conditions back on Earth when the Envoy returns millennia later but will continue to reread the novel, expecting to notice some new details in the remaining 100+ pages.

I have also reread much of Alan Moore's Watchmen. Both of these very dissimilar authors are masters of several genres, albeit mainly in different media. I have listed Anderson's genres more than once before. It may be of interest to compare Moore's slightly different list:

Anderson

science fiction

fantasy

historical fiction

detective fiction

historical fantasy

heroic fantasy

historical sf

humorous sf

maybe two ghost stories?

Moore

science fiction

fantasy

horror

superheroes

fictional ads and political propaganda

a historical novel

a ghost story

pornography

contemporary fiction

a screen treatment

Someone will now tell me what I have missed from either list.

Saturday, 23 May 2015

Watchmen

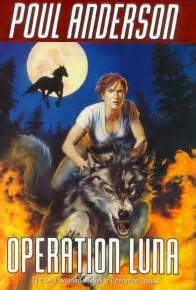

(Far out. One image gives us the cover of my edition of Watchmen and the Awesome Mage himself.)

I am rereading Alan Moore's Watchmen so I need an angle to discuss it on the Poul Anderson Appreciation blog. Easy. It is all in the alternative histories.

Poul Anderson gives us alternative histories in which:

the Carolingian myths were true;

William Shakespeare was not the Great Dramatist but the Great Historian;

technology was based not on science but on magic.

And Alan Moore gives us alternative histories in which:

when superhero comics inspired real life superheroes, comic books turned instead to pirates and, after the New York incident, to horror;

Superman and Captain Marvel were comic book characters but Mick Anglo's Marvelman was a parareality program and Moore's revived Marvelman was the real thing.

Absolutely Mind-blowing.

I am rereading Alan Moore's Watchmen so I need an angle to discuss it on the Poul Anderson Appreciation blog. Easy. It is all in the alternative histories.

Poul Anderson gives us alternative histories in which:

the Carolingian myths were true;

William Shakespeare was not the Great Dramatist but the Great Historian;

technology was based not on science but on magic.

And Alan Moore gives us alternative histories in which:

when superhero comics inspired real life superheroes, comic books turned instead to pirates and, after the New York incident, to horror;

Superman and Captain Marvel were comic book characters but Mick Anglo's Marvelman was a parareality program and Moore's revived Marvelman was the real thing.

Absolutely Mind-blowing.

Monday, 10 September 2012

Poul Anderson On Comics

Poul Anderson wrote many works of fiction in prose but not in the visual media of cinema or comic books. I have found three references to comics in his novels.

(i) In There Will Be Time, time traveller Jack Havig comments that, despite Superman's telephone kiosk, the most convenient place in a modern city for a time traveller to disappear is a public toilet cubicle.

Greek dramatists sometimes commented on and corrected errors or implausibilities in the works of their predecessors. In this vein, in the first Superman film, Clark Kent, responding to an emergency, approaches a public telephone that is not even enclosed in a kiosk, realises that it would afford him no privacy for a costume change and instead uses a revolving door at super speed.

Thus, the film, like Anderson, comments on a familiar scene from earlier Superman comics.

(ii) In Operation Luna (New York, 2000), Steve Matuchek remarks:

"It's only comic-book heroes and their ilk who bounce directly from one brush with death to the next, wisecracking along the way. Real humans react to such things." (pp. 158-159)

Yes, real humans in real life and in realistically written novels or comics. There is nothing in the latter medium that obliges that it be written unrealistically.

(iii) Matuchek also speaks against vigilantism even if conducted in "...comic book costumes" (p. 140). Right. Again, comics comment on earlier comics. Frank Miller's Batman is a vigilante wanted for assault, breaking and entering, child endangerment and, when the Joker's dead body has been found, murder. In Alan Moore's Watchmen, the public demonstrates and the police strike ("Badges, not Masks") until anonymous vigilantism is banned. In Garth Ennis' The Boys, superheroes are untrained and get a lot of people killed on 9/11. So the critique of comic book implausibilities is conducted in comics.

I would like to see high quality film and graphic adaptations of Anderson's works.

Later: For a fourth reference to comics, see here.

(i) In There Will Be Time, time traveller Jack Havig comments that, despite Superman's telephone kiosk, the most convenient place in a modern city for a time traveller to disappear is a public toilet cubicle.

Greek dramatists sometimes commented on and corrected errors or implausibilities in the works of their predecessors. In this vein, in the first Superman film, Clark Kent, responding to an emergency, approaches a public telephone that is not even enclosed in a kiosk, realises that it would afford him no privacy for a costume change and instead uses a revolving door at super speed.

Thus, the film, like Anderson, comments on a familiar scene from earlier Superman comics.

(ii) In Operation Luna (New York, 2000), Steve Matuchek remarks:

"It's only comic-book heroes and their ilk who bounce directly from one brush with death to the next, wisecracking along the way. Real humans react to such things." (pp. 158-159)

Yes, real humans in real life and in realistically written novels or comics. There is nothing in the latter medium that obliges that it be written unrealistically.

(iii) Matuchek also speaks against vigilantism even if conducted in "...comic book costumes" (p. 140). Right. Again, comics comment on earlier comics. Frank Miller's Batman is a vigilante wanted for assault, breaking and entering, child endangerment and, when the Joker's dead body has been found, murder. In Alan Moore's Watchmen, the public demonstrates and the police strike ("Badges, not Masks") until anonymous vigilantism is banned. In Garth Ennis' The Boys, superheroes are untrained and get a lot of people killed on 9/11. So the critique of comic book implausibilities is conducted in comics.

I would like to see high quality film and graphic adaptations of Anderson's works.

Later: For a fourth reference to comics, see here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)