Poul Anderson, Time Patrol (New York, 2006).

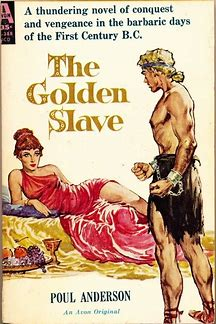

In Roman history and in Poul Anderson's historical novel The Golden Slave, the Roman general Marius halted a barbarian invasion of Italy. Marius is mentioned in Anderson's Psychotechnic History and in Poul and Karen Anderson's King of Ys Tetralogy and also, I am fairly sure, in other works by Poul Anderson. I have discussed Marius more than once here.

Here he is again - or rather his absence is here, in another timeline. Because the Romans lost the Second Punic War, the Punic Wars are called the Roman Wars and there was no army of the Roman Republic led by Marius to oppose that barbarian invasion:

"'About a hundred years after the Roman Wars, some Germanic tribes overran Italy.' (That would be the Cimbri, with their allies the Teutones and Ambrones, whom Marius had stopped in Everard's world.)" (pp. 201-202)

Because the two histories diverged so long ago, the only language in common between Everard and a citizen of Ynys ar Afallon is ancient Greek. Everard once had a job in Alexandrine times and Deirdre Mac Morn is a Classical scholar who performs Greek drama. ("Mac" means "son" so a patronymic has become a surname, as in our timeline.) The disappearance of Rome from history becomes clear when Everard says:

"'I speak Latin too.'

"'Latin?' She frowned in thought. 'Oh, the Roman speech, was it not? I am afraid you will find no one who knows much about it.'" (p. 188)

(I keep trying to halt the forward momentum of this blog so that I can apply some attention to alternative activities. I have again reached a round number of posts near the end of a month so this might be a breathing space. Meanwhile, I would like to hear from blog readers. If anyone out there can find time to "comment" by saying who they are, where they are and how they came to be interested in Poul Anderson, that would be appreciated.)

Addendum, 24 Feb '14: As I thought, Marius is mentioned during a political and historical discussion in Poul Anderson's futuristic sf novel, Shield (New York, 1970), p. 86.

Showing posts with label The Golden Slave. Show all posts

Showing posts with label The Golden Slave. Show all posts

Monday, 24 February 2014

Sunday, 16 December 2012

Chapter VI

(The image shows the cover of another book that identifies Harald Hardrada as "The Last Viking.")

On page 125 of Poul Anderson's The Golden Horn (New York, 1980), Harald is "...nearing the ripe age of twenty five years..." so I had calculated his age correctly in a recent post.

On page 124, Harald speculates on the place of origin of the Aesir, until recently worshiped as gods. The human originals of these Norse deities are thought to have come from around the Black Sea area about the time of Christ. In particular, Harald notices that the place names "Asgorod" and "Azov" are similar to "Asgard."

And, indeed, in Anderson's The Golden Slave, a one-eyed man called "Eodan" and his companion, Tjorr, led people called the Rukh-Ansa north from near the Azov Sea just before the time of Christ. Here is another strong connection between two works by Anderson and a further reason to read his historical fictions in their historical order. Harald has now referred directly to Gunnhild and indirectly to Eodan, both of whom we have already met if we have read the novels chronologically.

On page 125 of Poul Anderson's The Golden Horn (New York, 1980), Harald is "...nearing the ripe age of twenty five years..." so I had calculated his age correctly in a recent post.

On page 124, Harald speculates on the place of origin of the Aesir, until recently worshiped as gods. The human originals of these Norse deities are thought to have come from around the Black Sea area about the time of Christ. In particular, Harald notices that the place names "Asgorod" and "Azov" are similar to "Asgard."

And, indeed, in Anderson's The Golden Slave, a one-eyed man called "Eodan" and his companion, Tjorr, led people called the Rukh-Ansa north from near the Azov Sea just before the time of Christ. Here is another strong connection between two works by Anderson and a further reason to read his historical fictions in their historical order. Harald has now referred directly to Gunnhild and indirectly to Eodan, both of whom we have already met if we have read the novels chronologically.

Monday, 22 October 2012

Gratillonius

Poul Anderson's The Dancer From Atlantis features the originals of Theseus and the Minotaur;

Eodan, the hero of Anderson's The Golden Slave, is compared to Theseus when he throws a bull;

Gratillonius, the hero of Poul and Karen Anderson's Roma Mater (London, 1989), revisiting his family home, sees:

"...Theseus overcoming the Minotaur on a wall." (p. 45)

References to a common stock of mythical figures run through several of Anderson's works.

Gratillonius' family has preserved books copied on scrolls, not bound in codices - the latter more like modern books. The scrolls include The Aeneid which he had enjoyed. My current purpose in relearning Latin is to read The Aeneid. Like me, Gratillonius is British and had not learned Greek so I feel some kinship with him but I hope that, if I had lived then, I would neither have practised a men-only religion, Mithraism, nor, later, have converted to Christianity. A philosophical Paganism strikes me as an appropriate perspective from which to contemplate, and hopefully to survive, the Fall of Rome.

At local Moots, Pagan social gatherings, I meet Dianics who sometimes practise women-only rituals but I do not feel inclined to respond by reviving the Mystery of Mithras! That Mystery might have been slightly more durable if it had at least linked up with a comparable female Mystery, making Mithraists' wives less likely to accept Christ and baptise their children.

The Wealth Of The Past

The connections between Anderson's various historical novels are clearer when they are reread successively. The tetralogy is rich in information not only about the by that time Christianised Roman Empire but also about other parts of Europe like the still Pagan Hivernia (Ireland) - the characters include a young man who will later be called St Patrick - and the mythical Ys.

So far, I have focused on what we are told about Irish gods and about the hero's deity, Mithras, the latter an early alternative to Christ. However, other details worthy of attention while rereading are:

the antecedents and history of Ys;

Ysan domestic life and politics;

the nature of the city's gods, the Three, and the role of its Witch-Queens, the Nine;

the various Challengers to Gratillonius' Kingship of Ys and what happens to them;

the network of resistance to Roman rule and Grallon's (Gratillonius') fruitful contact with it;

the aftermath, with Ys destroyed, Rome withdrawing, Christ triumphant, the beginning of the Dark Ages and the seeds of the Middle Ages (Gratillonius lived at the end of an age as we do now).

Friday, 19 October 2012

The Golden Slave: Conclusion II

To understand and cope with their environment, people count observed objects, recount remembered events and try to control future events either magically or technologically. Alan Moore suggested that some words still reflect a primitive period when enumeration, narration and divination had not yet come to be differentiated as distinct activities:

we cast spells, spell words and divide time into spells;

we tell tales but a teller counts money;

a narrative is an account but accounts are financial records;

a story or a vote can be recounted;

we write with grammar and wrote gramery in grimoires.

Odin is associated with witchcraft and wisdom. (Witches were "wise women.") In Poul Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), Eodan, the original of Odin, denies that he knows magical arts but insists that he thinks. Eodan's faithful follower, Tjorr, suggests that:

" '...to think is a witchcraft mightier than all others.' " (p. 260)

Without thought, we would not be able to think of witchcraft or of anything else. And, for Tjorr, reasoning is mysterious, therefore magical. His hammer is lucky and holds lightning.

North of the city Tanais, they join Tjorr's people, the Rukh-Ansa, warriors and horse-breeders whose chiefs reward bards with golden rings. (This last practice is familiar to readers of Anderson's Viking novels; The Golden Slave is pre-Viking.) They lead some of the Ansa north where, according to Snorri Sturlason, they brought long ships, horse-breeding, runes, military skills and wise laws. We have seen Eodan learn all this, and lose an eye " '...for wisdom...', " during the novel (p. 279). All that remains is to die and become Odin.

Strengthened by this heritage, the folk left the forests, built nations, overthrew Rome, peopled Europe and shaped England - and, although Anderson does not add this here, the USA.

we cast spells, spell words and divide time into spells;

we tell tales but a teller counts money;

a narrative is an account but accounts are financial records;

a story or a vote can be recounted;

we write with grammar and wrote gramery in grimoires.

Odin is associated with witchcraft and wisdom. (Witches were "wise women.") In Poul Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), Eodan, the original of Odin, denies that he knows magical arts but insists that he thinks. Eodan's faithful follower, Tjorr, suggests that:

" '...to think is a witchcraft mightier than all others.' " (p. 260)

Without thought, we would not be able to think of witchcraft or of anything else. And, for Tjorr, reasoning is mysterious, therefore magical. His hammer is lucky and holds lightning.

North of the city Tanais, they join Tjorr's people, the Rukh-Ansa, warriors and horse-breeders whose chiefs reward bards with golden rings. (This last practice is familiar to readers of Anderson's Viking novels; The Golden Slave is pre-Viking.) They lead some of the Ansa north where, according to Snorri Sturlason, they brought long ships, horse-breeding, runes, military skills and wise laws. We have seen Eodan learn all this, and lose an eye " '...for wisdom...', " during the novel (p. 279). All that remains is to die and become Odin.

Strengthened by this heritage, the folk left the forests, built nations, overthrew Rome, peopled Europe and shaped England - and, although Anderson does not add this here, the USA.

Thursday, 18 October 2012

The Golden Slave: Conclusion

In Poul Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), a passage that I earlier quoted in part deserves some further attention:

"Eodan thought sometimes that the North might welcome such a god, more humanly brave than the dark, nearly formless wild Powers of earth and sky." (p. 214)

Anderson shows us human progress occurring in Eodan's mind. To admire personal qualities instead of fearing natural forces is a definite advance.

Tjorr can tell that his king Eodan will be deified:

" 'Will you remember old Tjorr when they begin to sacrifice to you?' " (p. 260)

(A bit like "Remember me when you come into your kingdom.")

Eodan has a strange dream. He is the wind with:

"...the unrestful slain Cimbri rushing through the sky behind him." (p. 258)

- Odin leading the Wild Hunt.

He passes a bloody hound (Garm) en route to hell but finds that "...hell was dead, it had long ago been deserted..." (p. 258)

What is he foreseeing here? A secular age when people no longer fear a hereafter?

In his dream, centuries pass. He rides past his own grave mound:

"...which stood out on the edge of the world where the wind was forever blowing..." (p. 258)

In Anderson's The Time Patrol (New York, 1991), a time traveler believed to be Wodan/Odin has a son who:

"...stayed unrestful...folk said that was the blood of his father in him, and that he heard the wind at the edge of the world forever calling." (p. 239)

Eodan's dream was four centuries earlier. In that dream, on the sheltered side of the grave mound is "...the first flower of spring." (p. 258)

- death and renewal. Earth turns beneath him among stars - knowledge that Earth spins in stellar space?

Eodan and Tjorr fight Romans under a stone roof supported by a pillar (Yggdrasil) that Tjorr smites, thus bringing the roof down on their enemies while he and Eodan escape into a tunnel dug earlier. Eodan, wounded in his left eye and not at this stage expecting to survive, thinks, "...gods and demons die in the wreck of their war." (p. 273)

- a modest beginning for the myth of Ragnarok.

"Eodan thought sometimes that the North might welcome such a god, more humanly brave than the dark, nearly formless wild Powers of earth and sky." (p. 214)

Anderson shows us human progress occurring in Eodan's mind. To admire personal qualities instead of fearing natural forces is a definite advance.

Tjorr can tell that his king Eodan will be deified:

" 'Will you remember old Tjorr when they begin to sacrifice to you?' " (p. 260)

(A bit like "Remember me when you come into your kingdom.")

Eodan has a strange dream. He is the wind with:

"...the unrestful slain Cimbri rushing through the sky behind him." (p. 258)

- Odin leading the Wild Hunt.

He passes a bloody hound (Garm) en route to hell but finds that "...hell was dead, it had long ago been deserted..." (p. 258)

What is he foreseeing here? A secular age when people no longer fear a hereafter?

In his dream, centuries pass. He rides past his own grave mound:

"...which stood out on the edge of the world where the wind was forever blowing..." (p. 258)

In Anderson's The Time Patrol (New York, 1991), a time traveler believed to be Wodan/Odin has a son who:

"...stayed unrestful...folk said that was the blood of his father in him, and that he heard the wind at the edge of the world forever calling." (p. 239)

Eodan's dream was four centuries earlier. In that dream, on the sheltered side of the grave mound is "...the first flower of spring." (p. 258)

- death and renewal. Earth turns beneath him among stars - knowledge that Earth spins in stellar space?

Eodan and Tjorr fight Romans under a stone roof supported by a pillar (Yggdrasil) that Tjorr smites, thus bringing the roof down on their enemies while he and Eodan escape into a tunnel dug earlier. Eodan, wounded in his left eye and not at this stage expecting to survive, thinks, "...gods and demons die in the wreck of their war." (p. 273)

- a modest beginning for the myth of Ragnarok.

Mithradates

Poul Anderson wrote of the characters in his Hrolf Kraki's Saga (New York, 1973):

"To us, their behavior seems insanely egoistic..." (p. xx).

In ancient times, the rich and powerful were able to behave in ways that we would regard as childish. In Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), Mithradates rages when a woman whom he wants as a concubine absconds. I thought that his behaviour was infantile and Anderson confirmed this through the character Eodan:

"...the Cimbrian knew where he had seen such a look before - in small children, about to scream from uncontrollable rage." (p. 247)

Mithradates demonstrates his "Greatness" by mastering his rage sufficiently to dismiss the men who have been caught up in the drama of the unwilling concubine instead of taking any further action against them.

These men are Eodan and Flavius. Since Eodan is the original of Odin, could his opponent Flavius who smiles mockingly and moves like a cat be the original of Loki? Maybe, but Flavius' full name is Gnaeus Valerius Flavius and I do not find it possible to derive "Loki" from it.

"To us, their behavior seems insanely egoistic..." (p. xx).

In ancient times, the rich and powerful were able to behave in ways that we would regard as childish. In Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), Mithradates rages when a woman whom he wants as a concubine absconds. I thought that his behaviour was infantile and Anderson confirmed this through the character Eodan:

"...the Cimbrian knew where he had seen such a look before - in small children, about to scream from uncontrollable rage." (p. 247)

Mithradates demonstrates his "Greatness" by mastering his rage sufficiently to dismiss the men who have been caught up in the drama of the unwilling concubine instead of taking any further action against them.

These men are Eodan and Flavius. Since Eodan is the original of Odin, could his opponent Flavius who smiles mockingly and moves like a cat be the original of Loki? Maybe, but Flavius' full name is Gnaeus Valerius Flavius and I do not find it possible to derive "Loki" from it.

Mithraism

Poul Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980) shows that Mithraism was transitional:

" 'No lesser god enters the Presence of Mithras...'" (p. 200)

"...it was forbidden to call on him unless one had been initiated into his mysteries." (p. 214)

In Poul and Karen Anderson's King of Ys tetralogy, Gratillonius, a Mithraist, becomes King of Ys even though this makes him an incarnation of one of the Ysan gods - but his Mithraism also brings him into conflict with them.

Could Mithraism have become the Roman and European religion instead of Christianity? Only by changing and becoming more like Christianity. It would have had to:

become fully monotheist;

historicise the Mithraic myth;

initiate women;

replace sacrificial animals with a more convenient symbol like bread and wine;

maybe claim that its victim, slaughtered once, was perfect and sufficed for all time, thus the god himself rather than a bull - not Jesus the Lamb but Mithras the Bull?

Wednesday, 17 October 2012

Origins III

" 'Not that we would have much use for it in the North...and yet, who knows?' " (p. 204)

Here then is the origin of Norse runes.

Tjorr, rubbing his hammer, remarks, " 'There's luck in this old maul...Maybe even something of the lightning.'" (p. 213) He worships a thunder-snake. In mythology, Thor will control thunder and lightning and fight a serpent.

Mithras will lead the warriors who have been his guests in heaven to resist the final onslaught by the forces of evil.

"Eodan thought sometimes that the North might welcome such a god..." (p. 214)

Here are the origins of the Valkyries, Valhalla and Ragnarok.

Mithras was born of a virgin through the grace of the Most High "...that his followers might live in heaven after death..." (p. 214). Men feast and give presents on his midwinter birthday and the Cross of Light stands on his banners. Here are some of the origins of Christianity.

Mithras And The Bull

(i) The Three BC (Conan The Rebel, The Dancer From Atlantis and The Golden Slave);

(ii) The Time Patrol;

(iii) Ys.

(i) Mitra of the Sun is active in Conan The Rebel. The Dancer from Atlantis, a contemporary of Theseus and the Minotaur, dances with bulls. In The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), the Cimbri throw bulls at the spring rites. Phryne, the educated Greek slave, calls Eodan of the Cimbri, "Another Theseus!" (p. 36)

The conquering Cimbri travel with a great Bull idol, "...who was also in some way Moon and Sun...," in a wagon (pp. 15, 214). King Mithradates of Pontus, a Mithraist, wonders whether:

" '...the Bull in whose sign you wandered the world was the same that bleeds upon the altars of the Mystery?'" (p. 206)

(ii) In The Time Patrol (New York, 1991), the street cries of ancient Persia include:

" 'Alms, for the love of Light! Alms, and Mithras will smile upon you!...' " (p. 42)

"...the sign of the cross...was a Mithraic sun-symbol..." (p. 48)

In Cyrus' palace, a Time Patrolman looks up:

"Overhead he saw a painted roof, where a youth killed a bull, and the Bull was the Sun and the Man." (p. 56)

(iii) King Gratillonius of Ys, a Mithraist, sacrifices a white bull.

Christianity won the battle of ideas with Mithraism because it admitted women and replaced a sacrificial animal with bread and wine. There is still blood on the altar but sacramentally.

(I said in an earlier post that The Golden Slave shifted from Eodan's point of view to Phryne's for the first time in Chapter XIII but it had already done so in Chapter III. I need readers to point out mistakes.)

Tuesday, 16 October 2012

Literature, Philosophy and Mythology

In Poul Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), Flavius and other Roman prisoners plan a counter-mutiny on a ship captured by escaped slaves. Eodan, the slave leader, is roused from sleep to be told that several of his crew have already been killed. If the narrative had remained with his point of view, we would have had to learn of these events when he did but, by adopting another character's point of view for Chapter XIII, Anderson keeps us abreast of occurring events.

Flavius was Eodan's slave, then Eodan was Flavius'. Phryne, the educated Greek slave, calls this situation "...Euripedean..." (p. 35). Later, when Flavius has been Eodan's prisoner, he, an educated Roman, calls their relationship an " '...Iliad'." (p. 184)

Flavius knows not only literature but also philosophy and expresses the latter poetically:

" 'There are no free and unfree; we are all whirled on our way like dead leaves, from an unlikely beginning to a ludicrous end. I do not speak to you now; the sounds that come from my mouth are made by chance, flickering within the bounds of causation and natural law. Truly, we are all slaves. The sole difference lies between the noble and the ignoble.' " (p. 175)

Meanwhile, Anderson again prefigures the future role in Northern mythology of Eodan's first mate, the red-bearded, hammer-wielding Tjorr:

"...he sprawled against the weapon chest. His mouth was open and he made a private thunder in his nose." (p. 180)

Literary, philosophical and mythological allusions add depth to an exciting action-adventure narrative.

In Chapter XIII, the narrative point of view had shifted from Eodan to Phryne. Chapter XIV goes further, considerably broadening the perspective. The viewpoint character is now a sea captain, Arpad of Trapezus, carrying an ambassador from Pontus to Egypt. The King of Pontus, Mithradates, had been "...forced to flee the usurping schemes of mother and brother, living for years a hunter in the mountains, until he returned to wrest back his heritage." (p. 188) This kind of story is described as a heroic legend in the Time Patrol series.

On the fourth page of his viewpoint chapter, Arpad, on his return journey, rescues Eodan, Tjorr and Phryne from their foundering vessel so that now we read a description of these three characters as seen by Arpad.

Flavius was Eodan's slave, then Eodan was Flavius'. Phryne, the educated Greek slave, calls this situation "...Euripedean..." (p. 35). Later, when Flavius has been Eodan's prisoner, he, an educated Roman, calls their relationship an " '...Iliad'." (p. 184)

Flavius knows not only literature but also philosophy and expresses the latter poetically:

" 'There are no free and unfree; we are all whirled on our way like dead leaves, from an unlikely beginning to a ludicrous end. I do not speak to you now; the sounds that come from my mouth are made by chance, flickering within the bounds of causation and natural law. Truly, we are all slaves. The sole difference lies between the noble and the ignoble.' " (p. 175)

Meanwhile, Anderson again prefigures the future role in Northern mythology of Eodan's first mate, the red-bearded, hammer-wielding Tjorr:

"...he sprawled against the weapon chest. His mouth was open and he made a private thunder in his nose." (p. 180)

Literary, philosophical and mythological allusions add depth to an exciting action-adventure narrative.

In Chapter XIII, the narrative point of view had shifted from Eodan to Phryne. Chapter XIV goes further, considerably broadening the perspective. The viewpoint character is now a sea captain, Arpad of Trapezus, carrying an ambassador from Pontus to Egypt. The King of Pontus, Mithradates, had been "...forced to flee the usurping schemes of mother and brother, living for years a hunter in the mountains, until he returned to wrest back his heritage." (p. 188) This kind of story is described as a heroic legend in the Time Patrol series.

On the fourth page of his viewpoint chapter, Arpad, on his return journey, rescues Eodan, Tjorr and Phryne from their foundering vessel so that now we read a description of these three characters as seen by Arpad.

Monday, 15 October 2012

Origins II

"Eodan...thought...that if he built himself a boat in the North...open-decked, so a young man could pull his oar beneath the sky...." (p. 159)

That is the origin of the Viking long ships.

At the very end of the novel, Eodan, asked how he had lost an eye, replies, " 'I gave it for wisdom.' " (p. 279) That is the origin of the myth of Odin at Mimir's Well which is retold elsewhere in Anderson's works. Remembering my first reading of the novel, I expect also to find an origin for Valhalla.

(Before this, we have had Eodan wearing a hat and cloak, carrying a staff, and Tjorr fighting with a hammer, " '...a good weapon, though a little too short in the haft.' " (p. 141) If I remember the myths correctly, there was a reason why Thor's hammer was slightly too short.)

Meanwhile, an interesting moral question arises. The escaped slaves become pirates. They attack a merchant ship, kill some of its crew and steal its cargo. Is this a wrong thing to do? Yes, we would usually say so. However, on the captured ship, they not only steal wine and get drunk but also free slaves. Killing men who transport slaves might not be such a bad thing? Barbarians could regard themselves as permanently at war with the Romans who enslave them. This issue is compromised by the fact that Eodan was enslaved while attacking Rome.

And, of course, personal enrichment, not human liberation, was the motive for the pirate attack. A higher minded approach would have been to hail the merchant ship, demand that it release the slaves and only to attack if it refused.

Finally, for now, after twelve Chapters of Eodan's point of view, we have the surprise of a change to the point of view of one of his companions, Phryne, in Chapter XIII. Since that is currently as far as I have reread, any further comments will have to wait. (Tomorrow, Tuesday, 16 October, I will drive my son-in-law to a medical appointment, then study some Latin. We are reading a text about a fire in a Roman tenement of the kind that Eodan saw on entering the city.)

Cities

Yet again, I commend a descriptive passage by Poul Anderson when one of his characters, in this case Eodan in The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), enters a city.

Anderson shows us many cities:

fabulous, prehistoric, extraterrestrial, even extra-planetary;

an alternative Paris in a divergent timeline;

an alternative York in an AI "emulation";

memorably, the real York in Operation Luna.

In The Golden Slave, Eodan enters Rome, a city that is great:

in history and myth;

in Italy and Europe;

in Paganism and Christianity;

in the annals of Ys and of the Time Patrol.

Eodan had dreamed of "...golden roofs above white colonnades, shimmering against a sky forever blue...," then had experienced "...the avenue of the triumph..." as a captured slave. (p. 84) Now, he enters a real city to one of Anderson's descriptive lists, "...a city that toiled and played and sang and dickered and laughed..." etc. (p. 84) On the next page, there is a list of street smells.

We are told that Rome "...eternally outgrew her walls..." (p. 84). Well, she is the Eternal City. And there is one detail that we might recognize:

"...tall wooden tenements...the landless, workless scourings of war and debt crouched in their rags waiting for the next dole." (p. 85)

It seems that the Romans were just like us but with slaves instead of machines.

Anderson shows us many cities:

fabulous, prehistoric, extraterrestrial, even extra-planetary;

an alternative Paris in a divergent timeline;

an alternative York in an AI "emulation";

memorably, the real York in Operation Luna.

In The Golden Slave, Eodan enters Rome, a city that is great:

in history and myth;

in Italy and Europe;

in Paganism and Christianity;

in the annals of Ys and of the Time Patrol.

Eodan had dreamed of "...golden roofs above white colonnades, shimmering against a sky forever blue...," then had experienced "...the avenue of the triumph..." as a captured slave. (p. 84) Now, he enters a real city to one of Anderson's descriptive lists, "...a city that toiled and played and sang and dickered and laughed..." etc. (p. 84) On the next page, there is a list of street smells.

We are told that Rome "...eternally outgrew her walls..." (p. 84). Well, she is the Eternal City. And there is one detail that we might recognize:

"...tall wooden tenements...the landless, workless scourings of war and debt crouched in their rags waiting for the next dole." (p. 85)

It seems that the Romans were just like us but with slaves instead of machines.

Escape!

Quite often in Poul Anderson's fiction, our hero escapes from his enemies and spends quite a lot of time pursued and avoiding recapture. One way to make an initial escape is with a hostage. A high-ranking opponent, surreptitiously held at sword-point or at gun-point, can be forced to accompany the hero and his companion(s), thus concealing from the hostage's subordinates that an escape is occurring.

This sort of things happens in Ensign Flandry and The Golden Slave. In the latter novel, three escaping slaves, helped by a lot of good luck, force their owner to hire a ship and to accompany them on board. Inevitably, he escapes from them and alerts the crew that his three companions are mutineers. The three retaliate by freeing and arming the slaves who are the ship's cargo. Now there is a more even fight that will result in slaughtering the crew and capturing the ship. We are back to a more plausible sequence of events.

Escapes, pursuits and fights are necessary to the plots of action-adventure fiction which, moreover, Anderson wrote very well. However, it is several other features of his writing - the well-realised historical and speculative future periods, descriptive passages, characterisation and re-told myths and legends - that make us read and reread his works.

This sort of things happens in Ensign Flandry and The Golden Slave. In the latter novel, three escaping slaves, helped by a lot of good luck, force their owner to hire a ship and to accompany them on board. Inevitably, he escapes from them and alerts the crew that his three companions are mutineers. The three retaliate by freeing and arming the slaves who are the ship's cargo. Now there is a more even fight that will result in slaughtering the crew and capturing the ship. We are back to a more plausible sequence of events.

Escapes, pursuits and fights are necessary to the plots of action-adventure fiction which, moreover, Anderson wrote very well. However, it is several other features of his writing - the well-realised historical and speculative future periods, descriptive passages, characterisation and re-told myths and legends - that make us read and reread his works.

Sunday, 14 October 2012

Origins

When we are familiar with a heroic character or a mythical figure, we read with interest of his origin, how he came to be, how he acquired his name, powers, distinctive garb etc. Gospel accounts of Infancy, Temptations and the Word are Messianic origin stories. There are Buddhist accounts of why Gautama and his monks wore saffron robes and of how the word for "awakened" became a new religious title.

In the first Superman film, Lois Lane, having interviewed the title character, exclaimed, "What a super man!...Superman!" This is a version of the story in which the symbol on Superman's chest is Kryptonese, resembling the Roman "S" only by coincidence. He tells her that "Krypton" is "K. R. Y...", not "C. R. I...". Very funny. I would prefer a more serious treatment in which there cannot initially be any such thing as the correct way to spell an alien word in a terrestrial alphabet.

I have been told that the "Man With No Name" trilogy of Western films was made out of sequence, thus that the central character dons a familiar poncho for the first time at the end of the third film, at which point the audience realises that the events of this film precede the events of the first and second films?

The Simpsons TV cartoon series parodied origin stories. Bart and his friends saved to buy Radioactive Man, No 1. On the first page: " 'My body's glowing...It's radioactive...I'm radioactive...From this moment on, I am RADIOACTIVE MAN!' " Bart exclaims, " 'So that's how it happened!' "

I discuss origin stories because I have found an extremely understated example of such a story on pages 82 and 83 of Poul Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980). The escaping slave Eodan dons a disguise whose several items include a hat, a long cloak and a staff. This means nothing to the reader at the time. These items are listed among others and we do not yet know that Eodan will be remembered as a god.

He attributes his good luck while escaping to the fact that:

" 'A Power has been with me...' " (p. 110)

Maybe, but The Golden Slave is historical fiction, not historical fantasy. Thus, no Power is going to manifest except in the beliefs of some of its characters. Indeed, Eodan's Roman opponent asks:

" '...what educated man can take seriously those overgrown children on Olympus?' " (p. 110)

Instead, the Roman expounds a theory of blind matter obeying blind laws with events differentiated by "'...only the idiot hand of chance...' " (pp. 110-111).

(Ironically, I know a Pagan of Italian descent whose goddess is Fortuna and who sometimes makes decisions with dice.)

Back to Eodan. He frees some fellow slaves. They include a big man with a red beard who grabs and fights with a hammer, then names himself, " 'Tjorr...of the Rukh-Ansa...' " (p. 128).

I thought, "OK. Where's Odin?" Then I remembered that Eodan had been with us from the second sentence of the novel.

In the first Superman film, Lois Lane, having interviewed the title character, exclaimed, "What a super man!...Superman!" This is a version of the story in which the symbol on Superman's chest is Kryptonese, resembling the Roman "S" only by coincidence. He tells her that "Krypton" is "K. R. Y...", not "C. R. I...". Very funny. I would prefer a more serious treatment in which there cannot initially be any such thing as the correct way to spell an alien word in a terrestrial alphabet.

I have been told that the "Man With No Name" trilogy of Western films was made out of sequence, thus that the central character dons a familiar poncho for the first time at the end of the third film, at which point the audience realises that the events of this film precede the events of the first and second films?

The Simpsons TV cartoon series parodied origin stories. Bart and his friends saved to buy Radioactive Man, No 1. On the first page: " 'My body's glowing...It's radioactive...I'm radioactive...From this moment on, I am RADIOACTIVE MAN!' " Bart exclaims, " 'So that's how it happened!' "

I discuss origin stories because I have found an extremely understated example of such a story on pages 82 and 83 of Poul Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980). The escaping slave Eodan dons a disguise whose several items include a hat, a long cloak and a staff. This means nothing to the reader at the time. These items are listed among others and we do not yet know that Eodan will be remembered as a god.

He attributes his good luck while escaping to the fact that:

" 'A Power has been with me...' " (p. 110)

Maybe, but The Golden Slave is historical fiction, not historical fantasy. Thus, no Power is going to manifest except in the beliefs of some of its characters. Indeed, Eodan's Roman opponent asks:

" '...what educated man can take seriously those overgrown children on Olympus?' " (p. 110)

Instead, the Roman expounds a theory of blind matter obeying blind laws with events differentiated by "'...only the idiot hand of chance...' " (pp. 110-111).

(Ironically, I know a Pagan of Italian descent whose goddess is Fortuna and who sometimes makes decisions with dice.)

Back to Eodan. He frees some fellow slaves. They include a big man with a red beard who grabs and fights with a hammer, then names himself, " 'Tjorr...of the Rukh-Ansa...' " (p. 128).

I thought, "OK. Where's Odin?" Then I remembered that Eodan had been with us from the second sentence of the novel.

One Past And Two Futures

Because Poul Anderson's The Golden Slave (New York, 1980), set during the Roman Republic, is unadorned historical fiction that "...might have happened..." (p. 5), its timeline could incorporate our present and any of Anderson's fictitious futures. In fact, it resonates with two of the latter.

Anderson's first future history begins with a short story called "Marius" that refers to the Roman general Marius' victory over the Cimbrians which is the subject matter of The Golden Slave, Chapter II.

Eodan, a captured Cimbrian, describes enslavement:

" 'Not clean death, but marching in triumph, shown like an animal, while the street-bred rabble pelted us with filth! Chained in a pen, day upon day upon day, lashed and kicked, till we finally went on a block to be auctioned! And afterward shoveling muck, hoeing clods, sleeping in a hogpen barracks with chains on every night!' " (p. 50)

Anderson's second future history describes enslavement in the Terran Empire. In A Knight Of Ghosts And Shadows (London, 1987), the law requires slaves to wear a bracelet audiovisually linked to a global monitor net through which direct nerve stimulation to the brain can be administered. Not an auction block but a recording room where an enslaved woman is filmed to a running commentary:

" '...human female, age twenty-five, virgin, athletic, health and intelligence excellent, education good though provincial. Spirited but ought to learn subordination in short order without radical measures...' " (p. 24)

Anderson shows us that even slavery can be modernised and technologised. Eodan's plight does not seem remote.

Anderson's first future history begins with a short story called "Marius" that refers to the Roman general Marius' victory over the Cimbrians which is the subject matter of The Golden Slave, Chapter II.

Eodan, a captured Cimbrian, describes enslavement:

" 'Not clean death, but marching in triumph, shown like an animal, while the street-bred rabble pelted us with filth! Chained in a pen, day upon day upon day, lashed and kicked, till we finally went on a block to be auctioned! And afterward shoveling muck, hoeing clods, sleeping in a hogpen barracks with chains on every night!' " (p. 50)

Anderson's second future history describes enslavement in the Terran Empire. In A Knight Of Ghosts And Shadows (London, 1987), the law requires slaves to wear a bracelet audiovisually linked to a global monitor net through which direct nerve stimulation to the brain can be administered. Not an auction block but a recording room where an enslaved woman is filmed to a running commentary:

" '...human female, age twenty-five, virgin, athletic, health and intelligence excellent, education good though provincial. Spirited but ought to learn subordination in short order without radical measures...' " (p. 24)

Anderson shows us that even slavery can be modernised and technologised. Eodan's plight does not seem remote.

The Golden Slave

During that pause, Anderson gives us the kind of well-observed detail that enriches his texts:

"The wind mourned about the house, wailed in the portico and rubbed leafless branches together. Another rain-burst pelted the roof." (p. 41)

We are standing in the kitchen of the villa with the slaves, hearing the wind and the rain. In fact, here Anderson uses the literary "Pathetic Fallacy," the pretense that the elements reflect human feelings, mourning and wailing for Eodan's loss. I think that this is also an "Objective Correlative," objective conditions expressing subjective feelings?

Anderson as always describes the changing seasons. After the wind and rain:

"Each day the sun stood higher; each day a new bird-song sounded in the orchard. One morning fields and trees showed the finest transparent green, as if the goddess had breathed on them in the night. And then at once, unable to wait, the leaves themselves burst out and the orchard exploded in pale fire." (p. 45)

Rereading Anderson gives the opportunity to pause on these details instead of rushing ahead to find out how Eodan escapes from slavery.

Saturday, 13 October 2012

Conan And Marius

Conan is the central character of a novel whereas Marius is discussed by characters in a novel and a short story. Marius, good at soldiering and at nothing else, made the mistake of going into politics and causing chaos whereas Conan, disliking states, preferring barbarism to civilisation, had the good sense to stay with what he was good at. I understand that later in this multi-authored series Conan does become a king but I imagine that this involves one-man rule of a small kingdom with popular assent, a very different proposition from electoral office and power politics in the growing, soon to be imperial, Roman state.

Marius, a general, rallied Romans and annihilated barbarian invaders. Conan, a barbarian, inspired rebels who annihilated imperial invaders. Conan also performed the cinematic feat of swinging on a rope to attack his enemies from behind. Only in Poul Anderson's works is it possible to read both an assessment of the historical Marius' military and political careers and an addition to the fictitious Conan's military exploits.

More On Marius

" 'Gaius Marius...A plebeian, a demagogue, a self-righteous and always angry creature who actually boasts of knowing no Greek...His one lonely virtue is that he is a fiend of a soldier.' " (p. 18)

That fits with the account in Anderson's "Marius" which relates that the general used his military reputation to enter politics without understanding it, thus causing fifty years of corruption, murder and civil war. It also suggests that the viewpoint character of "Marius," Fourre, unjustly maligns his opponent, Reinach, when he says that the latter could have become another Marius.

Marius

In his short story, "Marius," two powerful men, Fourre and Reinach, meet to discuss the way forward for a devastated near future Europe. Fourre addresses Reinach as "Marius" and explains this nickname by describing the Roman general's victory over the Cimbri. Reinach is puzzled but flattered.

However, almost immediately, Fourre, in a carefully planned mutiny, deposes Reinach and explains this action by again referring to Marius. It seems that Marius used his military prestige to go into politics where he got it all wrong, unintentionally paving the way for Caesarism and the end of the Republic.

Fourre comments over Reinach's corpse, " 'I would like to think that I helped spare Jacques Reinach the name of Marius.' " (1)

(1) Anderson, Poul, The Psychotechnic League (New York, 1981), p. 28.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)