I am not away from a computer this week after all but maybe with less time to spend on it.

Often the context gives some idea of the meaning of a word but sometimes also we think we know what a term means until asked. When asked by a fellow pupil at school what "enigma" meant, I suggested "mystery" and was told that that would fit the context but I remained unsure. The dictionary said, "A mysterious person or thing," which is more specific.

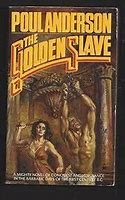

Anderson has a knack of using some vocabulary that remains baffling - until it is checked in a dictionary. Here is some more in

Rogue Sword (New York, 1960):

"...

morion..." (p. 172);

"...

shallop..." (p. 174);

"...

periplus..." (p. 222)

"...palomer..." (p. 261).?

The aspects of Anderson's works that I have come to monitor while rereading are:

wealth of vocabulary, as above;

clever use of language, particularly the disguising of verse as prose;

the author's control and deployment of the narrative point of view;

his occasional humor;

references to the seasons as showing the passage of time and also as displaying the "pathetic fallacy," i.e., the literary conceit that natural conditions reflect human feelings (in fantasy, they can also reflect divine feelings);

mastery of, and sometimes merging of, different genres;

connections between his works whether or not they belong to the same trilogy, tetralogy, series or even genre;

comparisons with Wells, Heinlein, Niven, Blish and Gaiman;

Anderson's values, with which he rightly challenges his readers;

his treatment of issues concerning the longer term development of society and humanity;

facts learned by reading his historical fictions;

his ability to render his characters' pre-scientific world views.

That list is longer than I expected it would be when I started to write it.

There is an odd momentary lapse in control of point of view in Rogue Sword. Lucas' return to his master's house is described from his point of view. However, as he approaches the opening gate, we are told that:

"The gatekeeper's mouth fell wide at the sight of the men in armor and the black-robed Dominican friar who accompanied them." (pp. 200-201)

The gatekeeper sees these men approaching behind the viewpoint character so they are described to us before he turns around and sees them. But, immediately after that, the narrative returns to Lucas' single point of view.