Sf still contains elements of the superheroes that have split off from it:

a mentally powered brotherhood resisting extra-solar invaders in James Blish's "Citadel of Thought";

Joel Weatherfield in Poul Anderson's "Earthman, Beware!";

The Un-men and the Sensitive Man in Anderson's Psychotechnic History;

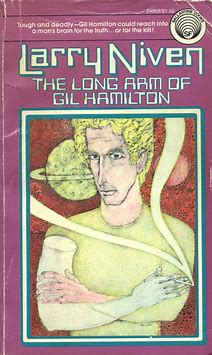

Gil the ARM Hamilton and the protectors in Larry Niven's Known Space future history;

Jack the Bodiless and Diamond Mask in Julian May's Galactic Milieu Trilogy.

Un-men and Sensitive Men could have been a forever series. Both would adapt well to screen.

21 comments:

The heroes of sagas and other similar schools of fiction -- Homer's poetry, for example -- are also "supermen", bands of brothers, etc. Batman is visibly a descendant of Robin Hood, etc.

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

I don't think that is correct. Batman did not rob from the rich and give the loot to the poor.

Not that it made sense think a BANDIT like Robin Hood would behave like that! Aside from some merchants, who were the wealthiest persons in England circa AD 1200? PROFESSIONAL military like knights and men at arms. You needed wealth to be able to buy the armor and weapons of those times--and the time and training needed to properly use them. I can't buy the idea of a poorly armed bandit like Robin tackling fully trained and equipped soldiers.

Robin Hood is better called Robbing Hoodlum! My sympathies are with the Sheriff of Nottingham, whose job was to keep the peace and enforce law and order.

Ad astra! Sean

Sean: Batman confronts evildoers... and plenty of aristocrats were, from a peasant's point of view.

He's also secretly a wealthy and powerful man himself; just as Robin Hood was often portrayed as an aristocrat himself, a King Richard loyalist persecuted by wicked King John and forced into being an outlaw.

He's also a great archer... and the English longbow was a powerful equalizer in itself.

It's not a matter of historical accuracy, but of familiar archetypes.

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

Of course I have to agree it was "...not a matter of historical accuracy, but of familiar archetypes." I was being opinionated and contrary!

I also thought longbows were not widely used till the English attempts at conquering France in the Hundred Years War.

And I still King John was a viciously slandered monarch, no where as bad painted by his enemies. Alan Lloyd wrote what I thought was a good defense of John in THE MALIGNED MONARCH.

Ad astra! Sean

Sean: he was -perceived- as a bad king rather widely. Not least because he didn't keep the baronage under control.

As for longbows, they were increasingly common in England throughout the 13th century, moving gradually westward from Wales through the midlands.

What wasn't available at first was a recognition of how deadly longbows could be and the tactics to use them with maximal effectiveness. Those were worked out in the Welsh marches in the course of the century.

The first big demonstration of the tactics that the English would use over and over was Dupplin Moor, in 1332, when a force of 1,500 English -- largely bowmen -- beat 15,000 Scots cavalry and heavy infantry. The English men-at-arms held the center, the bowmen were on the flanks, and the Scots got shot up to hell and gone.

Sean: he was -perceived- as a bad king rather widely. Not least because he didn't keep the baronage under control.

As for longbows, they were increasingly common in England throughout the 13th century, moving gradually westward from Wales through the midlands.

What wasn't available at first was a recognition of how deadly longbows could be and the tactics to use them with maximal effectiveness. Those were worked out in the Welsh marches in the course of the century.

The first big demonstration of the tactics that the English would use over and over was Dupplin Moor, in 1332, when a force of 1,500 English -- largely bowmen -- beat (at least) 15,000 Scots cavalry and heavy infantry.

The English men-at-arms held the center, the bowmen were on the flanks, and the Scots got shot up to hell and gone.

(Another feature was that the English were all volunteers, not levied.)

Incidentally, the Scots admitted 2,000-3,000 dead, and the English claimed over 10,000 Scottish dead.

The English casualties were precisely recorded: 2 squires, 33 men-at-arms and knights, and not one single archer.

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

As we both know, not all "perceptions" will be accurate. One of the things that impressed me about Alan Lloyd's book about King John was how he used that monarch's letters for shaping his judgment. According to Lloyd John's letters shows him as hard working, conscientious, a just judge,* and forgiving of injuries done to him. So, not a wholly bad man!

I think you meant to say the use of longbows spread eastwards from Wales. Yes, I can see it taking time for the English to grasp the potentialities of the longbow. And I had a vague idea they were first used with devastating effect against the Scots.

The Scots claimed "only" 2,000-3,000 killed at Dupplin Moor while the English said it was over 10,000? If we split the difference more or less evenly, then about 6,000 Scots died there. It was still a catastrophe for them!

Ad astra! Sean

*My recollection, true or not, was that King John was the last English monarch to personally hear trials and give judgments in what came to be called the Court of the King's Bench.

Sean: pardon the east-west lysdexia... 8-).

Incidentally, Richard was an effective warrior, but also a terrible king. John may have been a bit better as a king, but he was a lousy commander -- and that was an essential skill in the period.

One irony is that the English mythology of the war-bow emphasized individual marksmanship.

Because the way longbows were used -effectively- was in mass shooting at massed targets -- drenching a battlefield with arrows.

The 'secrets' of the longbow's tactical supremacy were rapid fire, long range, and heavy 'punch'. If one arrow didn't get you, another would.

It also required the other side to march right into the teeth of the arrowstorm. The French had a terrible record of doing this, even when they'd grasped that it was an invitation to disaster.

The Scots learned faster, except when they listened too much to the French.

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

I agree, the kings of John's time also had to be personally hands on soldiers. I do recall THE MALIGNED MONARCH arguing King John was not as bad a soldier as his enemies claimed.

I recall from your Emberverse books how the best way to use longbows was in massed volleys of arrows striking concentrated enemy forces.

Now I'm wondering, absent gun powder weapons, what would be the best way to handle long bow archers? A demonstration in strength, in front of them, just out of effective bow range, while other forces tried to attack the flanks?

Yes, the Scots were almost as slow as the French in figuring out how to handle long bow archers!

Ad astra! Sean

Sean: It's a general rule not to fight the way your opponent would like you to fight.

This is surprisingly hard to resist, though.

For example, if your enemy wants a major, decisive pitched battle you can refuse... but that means he can burn your country to the ground.

The English in the 100 Years War pulled that trick several times -- the

chevauchée' as it was called, massive raids to burn and plunder and kill until the French lost patience and did the bull-at-the-gate thing.

The Romans often used that technique against enemies who refused pitched battle; -vastatio-, "to lay waste", only they did it very thoroughly.

"They make a desert and call it peace", as Tacitus has a British observer comment on the way the Romans approached it.

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

I agree! In war don't fight as your enemy would WANT you to fight. Don't play to your enemy's strengths.

Again, I agree, vastatio can be very effective, as seen in your book TO TURN THE TIDE. But that won't always work, as Charles V of France demonstrated during his struggles with Edward III (and Edward's son the Black Prince). King Charles, assisted by his Constable, Bertrand du Guesclin, refused to be provoked by chevauchees into fighting pitched battles on unfavorable terms. The Constable's strategy was to wage guerrilla war on the English or force them into lengthy and costly sieges of French fortresses. By 1370 Charles V had regained almost all the territories he had been compelled to surrender in the Treaty of Bretigny.

The French even managed successful raids into England during Charles' reign. His admiral, Jean de Vienne, inflicted devastating raids on the southern coast of England from Plymouth in Cornwall to Gravesend near London.

Ad astra! Sean

Sean: it all depends on the relative balance of power.

The English simply weren't numerous enough, nor did they have enough of a generalized combat advantage, to 'devastate' France in the Roman fashion.

What the English had was a substantial advantage in -certain types- of pitched battles; most particularly, in ones in which they could get the French to attack them on ground of their own choosing.

When the French did that, the result was a disaster for them -- Crecy, Potiers, Agincourt.

It's a general paradox of warfare that to win, you ultimately have to attack successfully... but defending is simpler and easier than attacking.

Note that Henry V, the most successful English commander in the 100 Years War, not only won a great pitched battle -- Agincourt -- but also developed a strong siege train, including large cannon, and systematically reduced every fortress in his path.

And established an effective administration in the territories he took, which largely financed his operations, and enabled him to use substantial numbers of -French- troops.

In turn that produced large-scale defections among the French upper classes, helped along by the intense factionalism of French politics at the time and the bad leadership the French royal dynasty was afflicted with at the time.

If Henry had lived another 20 years, he'd probably have succeeded in uniting the realms... which would have been very bad for England, of course!

It illustrates that the ability to smash the other side's armies in pitched battles, while a massive advantage, isn't necessarily a complete answer.

Note also that it required very strong leadership and a degree of good luck to 'ignore' the English raiding strategy.

People in general expected their rulers to protect them from foreigners who burned, raped, plundered and killed.

If you failed in this duty, you risked defection and rebellion and loss of political legitimacy, and even complete collapse.

Hence the massive "jacqueries", peasant uprisings, in many parts of France during some phases of the 100 Years War.

From a peasant point of view, the aristocracy had failed in its basic duty -- maintaining at least some peace and security, so ordinary people could sow their crops with a reasonable expectation of reaping them.

And accordingly there was no reason not to kill them all.

Now, England had exactly one rebellion of note during the 100 Years War, namely Wat Tyler's revolt in 1381.

That wasn't in the least like the Jacquerie in France. It was a rebellion by (by the standards of the time) middle-class types, often ex-soldiers, with a specific political program, which they wanted the King to adopt.

The local gentry in the areas of the rebellion either joined it, or just pulled up their drawbridges and sat it out. It wasn't directed at them.

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

Very interesting comments, which I agree with.

Yes, until the French could finally handle how the English fought wars, the most effective response was to grimly tolerate chevauchees, despite the costs and risks, including widespread peasant revolts. Charles V had to contend not just with the English but also with Jacqueries.

Unfortunately for France, the intermittent madness of Charles VI from 1392 on, plus the bitter factional strife between Burgundians and Armagnacs, gave Henry V his great opportunity for conquering France after Agincourt in 1415. He might well have succeeded if Henry had not died young.

Ad astra! Sean

Mutiny and revolt are generally associated with -losing- wars. Note England's internal problems after the final defeat in France...

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

I agree. There were plenty of quarrels among the English leaders--beginning with bickering over HOW they could have lost a war they were winning in France.

Ad astra! Sean

One of the benefits of -winning- is that you can maintain internal harmony by 'paying off' rival factions/individuals with the -enemy's- land/possessions.

If you lose, you can't -- and that often leads to internal fighting.

Kaor, Mr. Stirling!

I agree, and that was exactly what William the Conqueror did in England after winning the Battle of Hastings.

And the final defeat of the English in France did lead to internal fighting in England. And it did not help that Henry VI was an ineffectual king unable to keep things under control by clamping down hard.

Ad astra! Sean

Post a Comment