Friday, 19 June 2015

Ppussjans And Hokas

"'...small, slim fellows, cyno-centauroid type; four legs and two arms...'" (Admiralty, p. 56)

Yet another quadrupedal race. How many in Poul Anderson's sf?

Regarding the Hokas, I do not buy intelligent alien teddy bears. On the one hand, the Hoka series is humorous sf. Therefore, its details are not meant to be taken too seriously. On the other hand, I would like to see a more serious treatment of this premise:

"'...my servant...does not consciously believe he's a mysterious East Indian; but his subconscious has gone overboard for the role, and he can easily rationalize anything that conflicts with his wacky assumptions...Hokas are somewhat like small human children, plus having the physical and intellectual capabilities of human adults. It's a formidable combination.'" (p. 58)

But is that not what we are? Protoplasm with an imagination? - that "...Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven as make the angels weep."

Genre Stories

In any case, a text should be self-explanatory. If a story is republished anywhere else, then its genre should be easily discernible, if not from the title, then at least from its opening passage. Poul Anderson and Gordon R Dickson needed to convey that "The Adventure of the Misplaced Hound" was:

science fiction;

an installment of an already existing series;

humor;

at least in part, a Holmesian pastiche.

They succeeded:

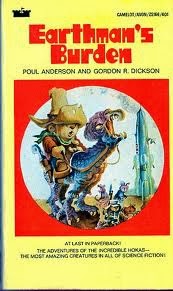

the story was published in Universe Science Fiction and collected in Earthman's Burden;

the title is Holmesian;

the opening sentence communicates humor by parodying a line from Gilbert and Sullivan;

the opening paragraph refers to the Inter-Being League, already familiar from previous Hoka stories, and also to the Interstellar Bureau of Investigation, clearly a detective outfit;

by the middle of the second page, we have learned that our regular hero and the visiting IBI man will visit the Tokan equivalent of England, where we might expect them to meet a Hoka Holmes, especially if we have noticed the cover of Earthman's Burden.

Wednesday, 4 December 2013

The Hoka Series As A Whole

The first story describes Alexander Jones' arrival on the planet Toka as an Ensign. From the third story, he is the plenipotentiary of the Interbeing League to Toka. The second story, written later, fills in the gap by describing a Tokan delegation to Earth and ends with Jones being appointed plenipotentiary.

The third, fourth, fifth and sixth stories are a linear sequence of events on Toka. After the sixth story, Jones writes a letter in which he states that, after an important baseball game, he will take a delegation to Earth to apply for an upgrading of Toka's status in the League.

The seventh story, to continue the numbering from the first volume, describes the baseball game. In the eighth, the delegation is on Earth but must surmount an obstacle to its application. The story ends with the obstacle overcome. The ninth story recounts what meanwhile happens to Jones' wife Tanni back on Toka.

The tenth story again starts with Tanni on Toka and recounts some events prior to the ninth story. When the action has again moved forward, Kratch obstruction to the Tokan application delays Jones on Earth while the situation on Toka deteriorates. If Jones does not return, the Tokan situation may become so catastrophic that the upgrading will be prevented and Jones' career ended but, if he is known to have returned, then the Kratch will stop obstructing parliamentary discussion of the Tokan application and have it debated without Jones there to put his case or reply to their objections.

Solution: Jones returns in secret. The story ends with the potential catastrophe averted but we still do not know the outcome of the application although it should be a foregone conclusion since the Kratch have been discredited as the fomentors of the crisis.

Thus:

the series, basically a comedy, becomes darker as it proceeds - the comic figures may be led into tragedy;

more could be told and I am yet to learn whether the novel, Star Prince Charlie, continues this narrative or goes off at a tangent.

Starting To Consider The Hoka Series As A Whole

When reading the first collection, Earthman's Burden (New York, 1979), I forgot to remind readers that the song "Sam Hall," of which a few lines are sung on p. 137, provided the name for a revolutionary alias in a Poul Anderson short story and that revolutionaries collectively called the Sam Halls were referred to in his novel, Three Worlds To Conquer.

One Hoka story ended with "THE WORDS": "Elementary, my dear Watson!" (p. 121) and the second collection ends with another famous quotation: "Publish and be damned!" (Hoka, New York, 1985, p. 240). The story states, and google confirms, that the Duke of Wellington commendably gave this advice to a would-be blackmailer. As with the pirates' names in the first volume, we learn a little history by reading the series, although a lot more from Anderson's historical and time travel fiction. I am sure that there is a reference to Colonel Blimp in Hoka although I cannot find it on re-scanning the text. Since Anderson also references Blimp in "Delenda Est" (Time Patrol), this time I googled and learned the history of this cartoon character, including the meaning of his surname.

Previously, I asked rhetorically why I was unable to deduce in advance what further use the authors would make of their superjovian-dwelling character, Brob. Sure enough, Brob makes himself helpful one more time in a way that follows logically from what we have already been told about his personality but that I was completely unable to anticipate.

Sunday, 1 December 2013

Resilience

There are some explanations. They are bad shots. They are also tough enough not to be injured when kicked by a brutal sergeant of the Foreign Legion. Their physical constitution is such that they can be hanged without being strangled or suffering a broken neck. A ship's captain who has been hanged by mutineers, after swinging around for a while, is cut down and deemed to have died so he quietly assumes a new role, like that of a fresh recruit to the ship's crew.

The Hokas' home planet, Toka, is Brackney's Star III. When the action moves to Teklo, Brakney's Star II, this theme of physical resilience continues. Telkan biochemistry works so fast that blood clots almost instantly and the Telks immediately recover from bullet wounds inflicted by the Hokas' black powder rifles. The Telks themselves fight with:

eggbeaters with sharp crank-turned blades;

scissors or shears for clipping off hands or head although Alex sees one Telk's six limbs knocking the blades aside;

mousetraps big enough for bears;

ladles for throwing corrosive acid which, however, only makes them scratch because "...they seemed too tough for serious damage..." (p. 185);

bouncing balls with poisoned needles;

pipes blowing a "...noxious weed to which the pipemen had cultivated an immunity..." (p. 177);

poison-covered tiddlywinks littering the ground to impede an enemy advance.

When the Telkan biochemistry in airborne yeasts energetically ferments brewing Hoka beer, a new weapon is forged: beer bottles with knife blades in the corks. When the corks are released, jets of liquid and blades hit the enemy, not killing anyone, just knocking them out for a few hours.

Well, I have carefully listed these absurdities expecting to find a point at which someone should surely die but maybe not?

Earthman's Burden: Concluding Remarks

I get mixed messages from Alexander Jones' concluding letter. On the one hand, he is:

"...shipping out for Earth in a few weeks..." (p. 187)

- but, on the other hand, he has:

"...changed [his] about resigning [his] position [on Toka]." (ibid.)

So the trip to Earth will be a holiday?

He adds:

"We have a Galactic Series Baseball game coming up shortly, but after that I'll be on my way." (p. 188)

Looking ahead, I gather that baseball is in progress on the opening page of the second volume so will there also be a trip to Earth? And will the four stories in the second volume cover as long a period of Jones' career as the six stories in the first? (I will just have to get on with reading the second volume.)

I have described the Hokas as "protean, not physically but mentally," so I am pleased to see that Jones refers to "...their protean imaginativeness..." (p. 188)

I also said that he was concerned about possible "cultural imperialism" and he now uses that same phrase (ibid.) but his "...doubts...are being resolved." (p. 187)

He rightly argues that:

"Their very adaptability is a protection against losing their racial heritage." (p. 188)

- although his next point is more questionable:

"It is, also, the special talent by which they may one day succeed us as the political leaders of the galaxy." (ibid.)

A possible sequel? I don't think so.

But, like all good comedies, the collection ends by treating its comic figures with affection and respect. Jones commends this "...sturdy, brave, independent little folk..." (p. 187) with their "...fundamental solid strength." (p. 188)

Swords And Science

Here is another logical consequence of the Hoka premise:

"...his anachronistic charges had recently led Alex to develop skill with sword, bow and lance..." (p. 174)

Of course! Not skills that a plenipotentiary would normally need or acquire but the circumstances on Toka are such that Alex must often defend himself with primitive weapons while thinking how to resolve a new impasse.

He reflects on his recently acquired military prowess because he is about to deal with the Telks who are neither tall nor tusked but nevertheless broad, hairless, muscular, green, four-armed, war-like and naked except for weapons. In other words, Telks sound like smaller T---ks (fill in the blanks), another sword-wielding race in an sf series.

OK. I must try to stop posting and finish reading.

A Little French

Jones, needing help to rescue his wife from the next planet sunward, begins, "My wife -," (p. 167) but breaks off when it occurs to him that he needs to be discrete about her current situation.

That single phrase, "My wife -," is enough for the civil governor of Sidi Bel Abbes. Getting Alex to confirm that he wants La Legion Etrangere, the governor rushes him to the commandant where my French is just enough for me to follow the comical dialogue on p. 168 -

Governor: La Femme -

Commandant: Non!

Governor: Mais oui!

Commandant: Avec un autre - un plus jeune-

Governor: On ne le dit pas; cependant...

I am not sure about "cependant" but, of course, the rest of it is -

G: The woman -

C: No!

G: But yes!

C: with another - a younger -

G: One doesn't say it...

So Alex must spend a few days under the brutish Sergeant LeBrute - Hokas are unaffected by kicks but not a human being - before he is able to desert in the company of a "typical" crew including a way over the top PC Wren-type Englishman called Cecil Fotheringay-Phipp Alewyn Smith. Since they "desert" in Alex's spaceship, they are at last en route to rescue his wife - but I will soon be en route for a Sunday afternoon drive with family to a local beauty spot so posting must cease for a while.

A Little History

Jones has learned to negotiate with the Hokas by accepting the terms of whatever is their current role instead of by trying to override it. At the end of the pirates story, he prevents what might have become a bloodbath by, just out of sight of the Hokas, as if in a radio drama, enacting a sword fight between two of his own personae, the plenipotentiary and a pirate admiral. This is appropriate since the entire pirates scenario is a drama in any case.

I had enjoyed the Holmesian London and was none too pleased to be yanked away from it into a fantastic piratical milieu but it became possible to learn a little history from the latter. The Hokas' "pirates" are either fictional, like Long John Silver, or historical, like Henry Morgan and Anne Bonney. I had not heard of Bonney but google confirms her historicity and I wondered whether she was related to William Bonney of whom we knew through "Western" fiction in the fifties. (Addendum: Or is she Anne Bonny?)

In the concluding story, Jones must rescue his wife from the natives of the next planet. This need not have been a Hoka episode but, of course, the story stays on message as Jones rounds up Hoka mercenaries from the desert where Arabs and Legionnaires are to be found. (His job has previously involved ensuring that they are not killing each other.) The story's title, "The Tiddlywink Warriors," the significance of which as yet eludes me (I am still reading), had not clarified what kind of Hoka sub-culture would be highlighted.

The natives of the second planet, treating Mrs Jones, as she thinks, like a goddess, are force feeding her with native food which is making her FAT, which is why she urgently requests rescue over the subspace radio. Surely there is an obvious alternative possibility, that they are fattening her up as a sacrificial victim...

A Mosaic World

the United States Cavalry and the Varangian Guard nearly fought as to which of them should provide an honor guard for a very important visitor but were overawed when King Arthur allied with the Black Watch;

the Secret Service escorts the very important visitor to the League Office which is guarded by a Samurai.

Thus already, we have briefly referred to six distinct sub-cultures. However, since this story is entitled "The Tiddlywink Warriors," I have yet to learn what its prevailing theme is to be.

So far also, we do not see any new marks of the passage of time. The Jones' offspring are still young enough to be referred to as "...the children..." (p. 161) and there is as yet no mention of a fourth. Alex has been married to Tanni long enough not to admit something to her but we are not told how long that is.

A convenient break from child care is provided by sending:

"...the children to the Hoka London to watch Parliament; he had hopes of government careers for them, and this was an unparalleled education in how not to conduct such business." (p. 161)

An excellent observation. Of course, Anderson and Dickson are merely treating their fictitious Hoka as objects of humor but many of my countrymen would make the same remark about the original London Parliament.

I do not think that the Jones' children will grow up and have children before the end of the third volume. Thus, I do not think that the Hoka series approaches future history status but, even if it did, I would qualify that classification. In Classical literature, an epic is a long heroic poem whereas a mock epic, like Metamorphoses, is epic in form though not in content. Since the Hoka series is not serious speculative fiction, to extend it to further generations would be to transform it only into a mock future history.

Addendum: OK, we do have a mark of the passage of time:

"Alex was hardened, after a dozen years on Toka." (p. 162)

Jones' Doubts

One way to generate drama in an installment of a series is to imply an imminent and fundamental change to some aspect of this familiar set-up - that the central character is about to resign or retire, for example. The interlude is a letter from Jones in which he says that he has not yet reached a definite decision about whether to resign but that, pending the result of an inspection, he "...shall very probably step aside..." (p. 157). This letter strikes a reflective note by contrast with the humor that is the main theme of the series - and it is appropriate that characters in a comedy are occasionally presented more seriously as when contemplating their future careers.

Jones doubts the value of the Cultural Development Service. He asks whether their work "...is only a subtler form of the old, discredited imperialism of Earth's brutal past?" (p. 156) As Anderson argues in other series, because each planet is economically self-sufficient, interstellar economic imperialism is both impossible and unnecessary. I think that this alone saves the CDS from rerunning British imperialism. There is nothing "brutal" about Jones' relationship with the Hokas.

But he goes on to expound his question differently:

"Have I merely been turning my wards into second-rate humans, instead of first-rate Hokas?" (ibid.)

This would be cultural imperialism. The question is complicated by the fact that a first-rate Hoka is precisely one who enacts an imported culture instead of developing his own. For this reason and no other, Jones has helped the Hokas, for example, to transform a Tokan island into "England" complete with London and rural shires.

Often, in a series, the drama of an episode is resolved as the fundamental change is prevented. In one episode of The Prisoner, the title character escapes and gets all the way back to London but winds up at the end of the episode back in the Village. Since there are two further Hoka volumes and since also I expect the narrative framework to remain much the same, I do not expect Jones to resign his post at the end of this first volume.

Saturday, 30 November 2013

The Sound And The Furry

"Holmes himself dropped into an armchair so overstuffed that he almost disappeared from sight. The two humans found themselves confronting a short pair of legs beyond which a button nose twinkled and a pipe fumed."

- Poul Anderson and Gordon R Dickson, Earthman's Burden (New York, 1979), p. 101.

The button nose, like the elsewhere mentioned beady eyes, make it difficult to avoid the impression that the Hokas are not just small and bear-like but really are animated toy teddy bears.

Anderson and Dickson reasoning logically from their own premises have invented an original crime, if not an Original Sin: smuggling historical novels to Toka! As the series proceeds, it does address some of the potential practical problems implied by its own premises. For example:

"...imposed cultural patterns were always modified so as to exclude violence." (p. 126)

Jones, the plenipotentiary, has to control the input. Thus, Hokas are able to read about bloodthirsty pirates only when inappropriate material has been smuggled in to them but then two dozen ships turn pirate, head for the Spanish Main and can be expected, irresponsibly, to attack Bermuda, "[n]ot really realizing it'll mean bloodshed. They'll be awfully sorry later." (p. 127)

Not realizing? Sorry later? That does raise some questions about their supposed intelligence.

When I asked in an earlier post whether Caesar would accept assassination etc, there was one such question that could have been answered affirmatively: would Dick Turpin accept being hanged? Tanni thinks that the Hokas have turned violent when she reads that they have hanged Dick Turpin but they do it every week: Hokas cannot be harmed by hanging them because "Their neck musculature is too strong in proportion to their weight." (p. 126)

Time Is Passing

The framing sequences and character continuity in Poul Anderson's and Gordon R Dickson's Earthman's Burden (New York, 1979) are provided by Alexander Jones who:

(i) visits Toka as an ensign in "The Sheriff of Canyon Gulch";

(ii) is visited by his fiancee, Tanni, while hosting Hokas on Earth in "Don Jones";

(iii) accompanied by his wife, Tanni, is plenipotentiary to Toka in "In Hoka Signo Vinces";

(iv) has been plenipotentiary for nearly ten years in "The Adventure of the Misplaced Hound";

(v) mentions the birth of their child in a letter appearing as an interlude between "The Adventure..." and "Yo Ho Hoka!"

I will look out for further such marks of the passage of time while reading the series.

In Isaac Asimov's Robot stories, character continuity is provided not by any of the robots but only by the woman and men (robopsychologist, trouble shooters, US Robots executives and representatives etc) dealing with the robots. Jones performs exactly this role with the Hokas, heading off trouble or dealing with it when it arises.

In fact, he shows that he is aware of the potential dangers to which I alluded in the immediately preceding post:

"Can you imagine what would happen if I admitted a band of preachers who not only read from the Old Testament - and won't give our local rabbis a chance to explain the details - but hand out illustrated biographies of Oliver Cromwell?" (p. 123)

Yea, verily. Exactly so. Jones' job is to prevent disasters and to keep the series on the comic level.

Hokas are protean, not physically but mentally. They have no language, traditions, stories or world-view of their own that they want to preserve. They must have had something originally but they don't want to preserve it. Instead, they eagerly, energetically embrace and live whatever myth, fiction or drama they receive from human beings, even including the English language suitably adapted to different contexts.

I wanted to read more about Holmesian London but that is not the point of the series. When Jones, still within the Hokan "England," goes to Plymouth, he is about to encounter pre-Holmesian pirates.

Another Science Of Mind

"The [Hokas] were linguistic adepts, and between their natural abilities and modern psychography had learned English in a matter of days."

- Poul Anderson and Gordon R Dickson, Earthman's Burden (New York, 1979), pp. 17-18.

This tells us only that the science is called "psychography," that it speeds learning and that it works on other species as well as on humanity but that is quite a lot to be told in a single sentence. The role of the new mental science in this narrative is merely to rationalize how one previous expedition from Earth has enabled an entire planetary population to speak fluent English in diverse dialects by the time our hero arrives with the second expedition.

Therefore, we hear no more about psychography, at least not in the parts of the series that I have read so far - the first four of the six stories in the first of the three volumes. It would have been interesting to learn more about the psychographic study of the Hokas since this species combines the strength and intelligence of human adults with the imaginative playfulness of human children. This contrast combined with the Hoka's resemblance to animated teddy bears is deployed for comic effect but could potentially have been the basis for a more serious treatment of alien psychology.

Anderson's "The Saturn Game" presents adult human beings immersing themselves in a psychodrama until, to ensure their own physical survival, they must imagine the deaths of their assumed characters.

An Elder Race Of Great Galactics

But to return to the Elder Race as a mere idea, there is no Space Patrol in known space but nevertheless a potentially imperialistic race reports that its new space battleship was devastatingly attacked by a smaller ship of the Space Patrol. Alexander Jones must suppress the fact that that was his ship hijacked by Hokas enacting a TV space opera. One possibility suggested by Jones is that:

"...the affair is a case of mistaken identity, possibly involving some as yet unknown race."

- Poul Anderson and Gordon R Dickson, Earthman's Burden (New York, 1979), p. 90.

This suggestion is enthusiastically endorsed and extended by Jones' bureaucratic superior. The Council of the Interbeing League is informed that an undiscovered alien race knows English and possesses a Space Patrol whose observed actions have been beneficial. A search begins for these aliens provisionally regarded as "...an elder race of Great Galactics..." (p. 91) whose Observers maintain the Space Patrol and who will be able to teach the League much.

Thus is born a major myth...

Laugh Out Loud Moments

(You folks out there have been great with page views recently: 190 yesterday; 125 by 11.10 am today. Maybe everyone who views can comment just once to tell us who and where they are?)

One, not the only, laugh out loud moment - an Interstellar Bureau of Investigation agent, responding to a role-playing Hoka:

"...caught on and nodded as if it hurt him. 'Of course,' he said in a strangled voice. 'I would be the last to compare myself with Mr. Holmes.'"

- Poul Anderson and Gordon R Dickson, Earthman's Burden (New York, 1979), p. 98.

Jones and the IBI man have flown to the Tokan island of England and landed in Victorian London with its peaked roofs, winding cobbled streets, River Thames, Buckingham Palace, Parliament, St Paul's still being built, fog, gas lamps, Scotland Yard, cockney policeman referring to "...'Er Majesty...'" (p. 97), Inspector Lestrade, hansom cabs pulled by large reptiles, 221-B Baker Street, Mrs Hudson and, of course...

Elementary...

"Through a great thundering mist, Alexander Jones heard THE WORDS.

"'Not at all. Elementary, my dear Watson!'"

- Poul Anderson and Gordon R Dickson, Earthman's Burden (New York, 1979), p. 121.

It had to happen.

People rightly say that Holmes never said that. But then why is it attributed to him? There are reasons why I think that it is a legitimate quotation. It would be more accurate if it were punctuated, "Elementary...my dear Watson!" but that is grammatically awkward.

(i) Holmes does say, "Elementary."

(ii) He does say, "My dear Watson."

(iii) Once, and I am not going to look it up now, he says both in quick succession in the course of a single conversation over two or three pages.

Therefore, it is legitimate:

to infer that Holmes would have said THE WORDS at some time in an off-stage conversation;

to attribute THE WORDS to him in some of the many sequels and adaptations.

In Casablanca: I think that the line "Play it again," is addressed to a character called Sam, hence that other spurious quotation, "Play it again, Sam."

A Few Miscellaneous Remarks

"The Sheriff of Canyon Gulch" (1951) shows Jones arriving on Toka as an ensign whereas "In Hoc Signo Vinces" (1953) shows him installed as plenipotentiary to that planet. "Don Jones" (1957), apparently written for the collection, fills in the gap by describing the Hokas' visit to Earth and Jones' appointment as plenipotentiary.

When the narrative refers to the "...beady eyes..." (p. 20) of a Hoka, it is difficult to avoid the impression that Jones is conversing with animated toys, literal "teddy bears," rather than with organisms.

"In Hoc Signo Vinces" (1953) shares some features with Anderson's The High Crusade: because they do not know any better, primitives defeat an interstellar imperial power.

"The Adventure of the Misplaced Hound" (1953) advances the story by showing Jones after nearly ten years as plenipotentiary to Toka.

"'...the leader, known as Number Ten...'

"'Why not Number One?' asked Alex.

"'Ppusjans count rank from the bottom up.'" (p. 94)

This could be a comment on British political procedures. The Prime Minister, head of the government, always lives in 10, Downing St, London, near Parliament. Thus, the phrase "Number Ten" can, in appropriate contexts, mean the office of the person who is currently the Queen's first minister - not the tenth!

I look forward to reading the rest of this Holmesian story about the "Misplaced Hound."

Friday, 29 November 2013

"It Comes To The Same Thing"

"'Haven't you read the preliminary psychological reports? It seems that Hokas have a hitherto unknown type of mind - given to accepting any colorful fantasy as if it were real...nobody knows, yet, whether they actually and literally believe it at the time, or just play a role to the hilt, but it comes to the same thing.'" (p. 43)

It comes to the same thing!

Every being that is both social and individually self-conscious, i. e., on Earth, every human being, soon learns to play the role of a named person with a specific set of inner recollections and outer interactions. We need not identify completely with this role but must maintain it for practical purposes, e. g., I must remember and answer to my name, not to anyone else's. But I can also change my name to express an altered perception or understanding of the self, its relationships and responsibilities.

To take a new name in religion is not just to change the label on a parcel but also to express a new understanding of the contents. Each of us is a currently conscious organism that is more than the sum total either of its memories or of others' perceptions. I am now. Either in spontaneous awareness or in disciplined meditation, I can transcend that social/psychological construct called "Paul" or (fill in the blank).

We can be like a Hoka between roles.

(There is more on the Hoka stories but it will have to wait till tomorrow or the day after.)

Earthman's Burden II

Ensign Dominic Flandry works for the Terrestrial Imperial Space Navy, with headquarters in Archopolis in the Northern Hemisphere of Earth, and we first meet Flandry when he has crash landed on the extra-Solar planet, Starkad, named from Terrestrial mythology.

Ensign Alexander Jones works for the Terrestrial Interstellar Survey Service, with headquarters in League City, New Zealand, and we first meet Jones when he has crash landed on the extra-Solar planet, Toka, named from a native word for "earth."

How is it that Jones experiences no language problem when he meets his first Tokans? There was one previous expedition from Earth and the natives are extremely imitative, even down to exactly mimicking, in this case, English as supposedly spoken in the American Old West...

Maybe I can hold onto my sanity by continually remembering parallels with Anderson's other fictitious futures?

Addendum: Another similarity - both heroes must trek across part of the planet to rejoin their comrades who are based elsewhere and must get involved in local conflicts en route.